Shadows of a Century Past

With my long and winding wildflower journey looming large in the rearview mirror, I stepped back to move forward in the spring of 2024. Weary of instant messaging, LED lights, screens, yard blowers, sirens, pings, pangs, and notifications, I embarked on a refreshing spring-season adventure. I corralled a couple changes of clothes, a camera, a tripod, and snacks and headed toward the familiar Texas Hill Country village of Prairie Mountain to photograph traditional self-portraits. Driving through sparsely populated country roads with open space clear to the horizon, I looked forward to the images I would capture. When I arrived atop the hill of the tiny settlement, "1924" above the old schoolhouse door caught my attention. "One hundred years ago," I whispered to myself. I spent a few hours unwinding and photographing in the tranquil springtime air. Nearing sunset, I captured a transcendent image of myself, backlit and surrounded by wildflowers, a fitting tribute to this intersection of my photographic life.

As I stood on the hill past twilight, I couldn't help but reflect on the span of a hundred years, from 1924 to 2024. The significance of this hundred-year mark intrigued me. The shadows of a century past kept me keyed into something deeper, beneath the surface of the obvious forward movement. I stepped back onto the schoolhouse stairs and captured an indistinct image of myself, a transitory offspring of choices made long ago. While driving home in the cover of darkness, my thoughts drifted past forty years or more to an age of musty wine cellars, floral print wallpaper, robust Italians eating and bickering and eating again.

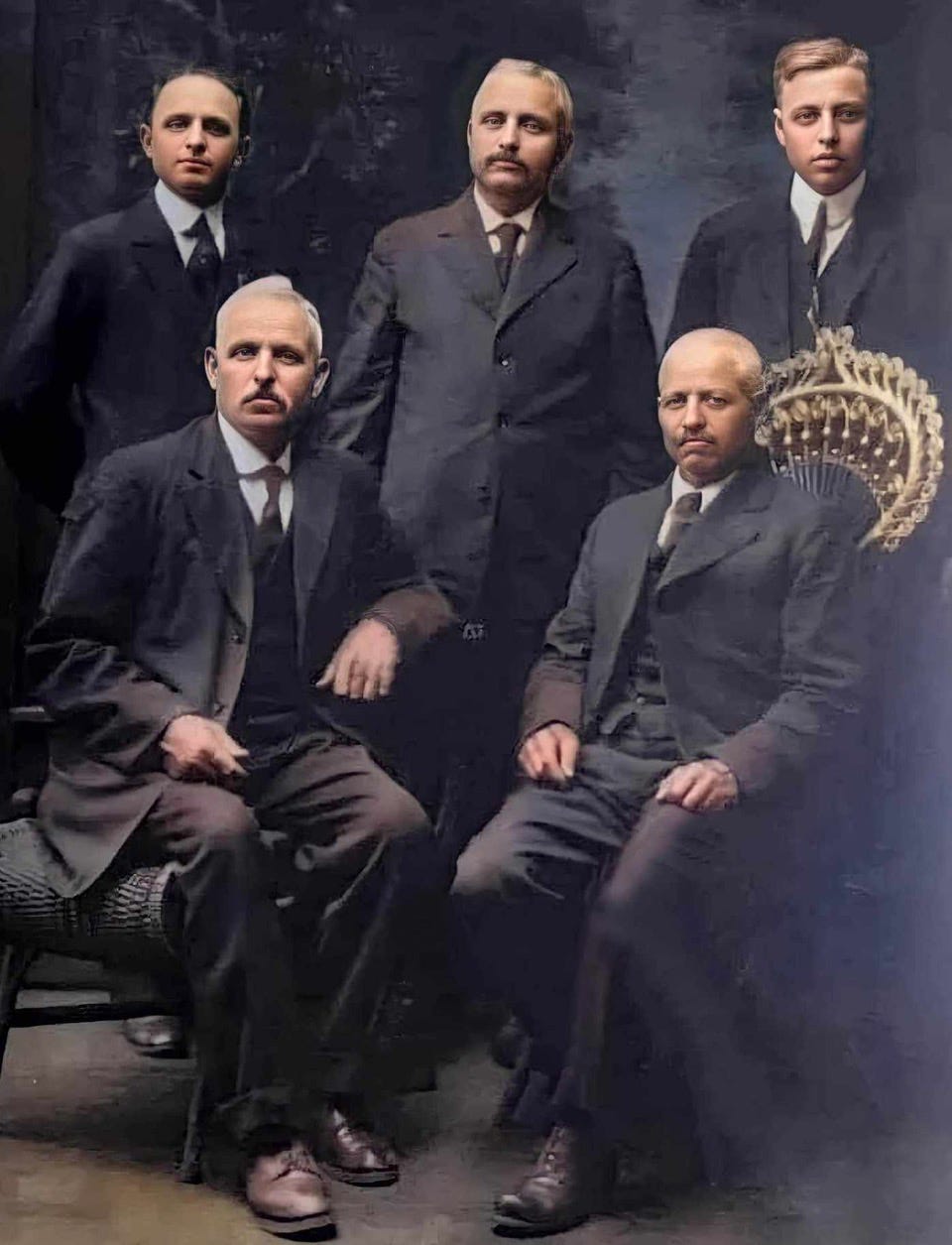

My paternal grandfather, Vincenzo DiMenno, was born on April 5, 1903, in Pollutri, Italy. He grew up in a home of limited means and often skipped school to play in the woods or along the shore of the Adriatic Sea. When his parents discovered his absences from the classroom, they gave him an ultimatum: "Go to school or go to work!" At the age of ten, he became a bricklayer's helper. When he was seventeen, Vincenzo set sail alone on the Lafayette from the port city of Le Havre in the Normandy region of northern France, arriving at Ellis Island on September 20, 1920. Through familial connections, an uncle from Italy hosted him in Rochester, New York. Eventually, Vincenzo settled in Batavia, a small town about forty-five minutes east of Buffalo. After finding steady work, he sent monthly checks of $2.00 back home to his parents in Italy, maintaining a connection with them through letters. Sadly, he never saw his family again.

My paternal grandmother, Theresa Marie Battaglia, was born on January 18, 1905, and was of Sicilian descent. Her parents immigrated to the United States independently from Sicily, both arriving at Ellis Island in the late 1800s. The Battaglia family also settled in Batavia, New York, where they became one of the wealthiest families in the area, owning a restaurant, a bar, and a farm on the outskirts of town. Theresa had eight brothers and one sister, though two sets of twins died at birth. My grandparents, Vincenzo (Grandpa) and Theresa (Granny), met in the Battaglia bar and were married a hundred years ago on June 8, 1924.

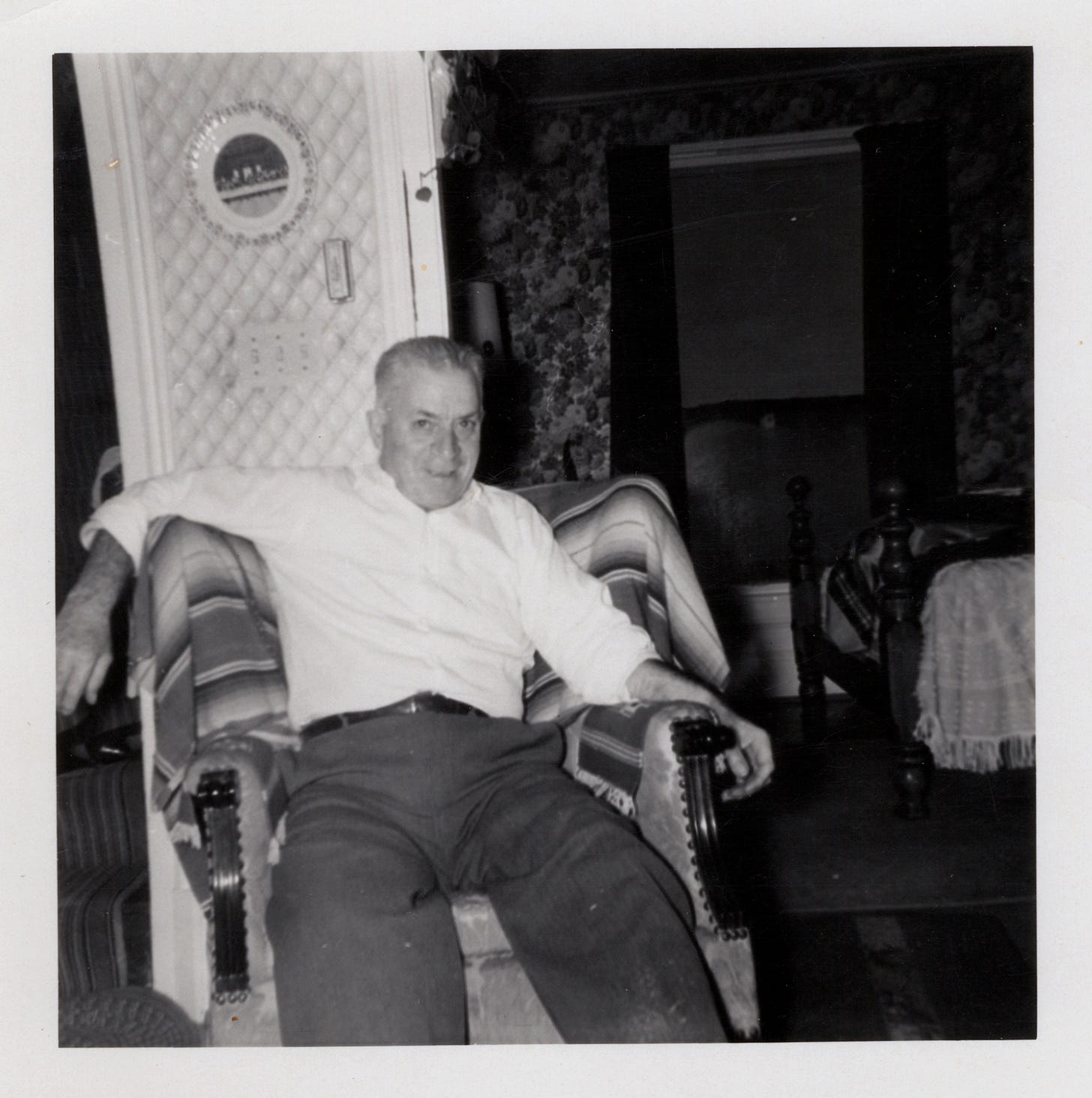

I remember my arthritic grandfather speaking in broken English about his journey to America from Italy. Although he didn't say much, when he did speak, his words, though limited, held substance. He was a simple man of simple values who enjoyed wine and song, homemade Italian food, beer, gin rummy, and the hot sun. Though he stooped over a cane, he moved with grace throughout his life.

Every spring, behind their two-story white wooden house on Ellicott Street, my grandfather planted a lush vegetable garden, using his cane to dig holes for seeds. Grandpa was a strong man, and despite the arthritis in his hips slowing him down, it didn't hinder his spirit. He drew energy from the sun and would sit for hours, seemingly deep in thought. His innocent laughter, endearing smile, sharp memory, and determination to tackle difficult tasks without complaint left a lasting impression on me.

My doting grandmother was a short, plump woman who spoke through her nose and carried a Kleenex in her dress pocket. I can still hear her prattling on about various topics while stirring spaghetti sauce, often complaining about her latest aches and pains. She talked more than she listened and seemed to have more energy than anyone in the room.

Although my grandmother's beliefs were archaic, her capacity for love was immense. Her faith in the Holy Catholic Church was unwavering. She was persistent and held tightly to her rosary, for fear if she let go, she might fall into a deep, dark void. She insisted I wear a long black mantilla on my twelve-year-old head as we walked the five or six blocks to Mass on Sunday mornings. She was a lively, dear woman with a big heart, slightly protruding front teeth, and a crooked smile. She gave the warmest, kindest, most loving hugs I've found anywhere.

Batavia is a small town that served as a resting place for many Italian immigrants. My grandmother's family, the Battaglias, were a tough bunch. Most of the men in their Sicilian lineage were intelligent yet harsh, rather than loving. My great-grandfather owned several businesses and had a beautiful home in the center of town. He was a shrewd businessman who roughed up his wife and children. My great-grandmother was quiet, meek, and worn out from having ten children and enduring ongoing abuse. At the age of sixty, my great-grandfather suffered a stroke. None of his eight sons, my grandmother's brothers, assisted with the businesses, which led to their father losing everything and falling into near poverty. The cycle of violence persisted, deeply affecting the brothers, who also abused their wives and children. Despite the abuse, my great-grandmother cared for her husband until he passed away thirteen years after his stroke.

Granny and Grandpa had four boys, and it was primarily my grandmother who raised them. She was strong-willed and a strict disciplinarian, managing the household with determination. As my dad shared, she would sometimes hold her rosary beads in one hand and a small whipping strap in the other. She would pray to God while also teaching her sons important life lessons.

My grandparents didn't have much awareness about raising a family, and my grandmother's upbringing was filled with victimization and mistreatment. Most of their communication was reactive or dismissive, with little, if any, discussion about anyone's feelings. Emotions were suppressed, only to explode or manifest later in other ways, and those behavioral habits were passed on to their sons. The lessons from their generation were softened in my father's generation, but there was still a noticeable influence in our household as we grew up, from both my father and my mother. My grandparents didn't live an examined life. They put one foot in front of the other, working hard to raise a family, living in relative poverty, doing the work, and putting in the time. Regardless, my father deeply loved both of his parents, and often remarked that my grandmother had a heart of gold.

Granny oversaw buying groceries, furniture, and clothing, as well as cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry. Every week during the school year, she would starch and iron five shirts for each of the four boys. She was always working, especially in the kitchen. She baked pies and Italian bread. My dad reflected, "Just visualize eating a thick slice of Italian homemade bread spread with olive oil, salt and pepper with fresh tomatoes right out of the garden. My life was great. We had everything we needed." Granny canned and pickled various foods, aside from what they ate fresh daily, including pears, watermelon rinds, cucumbers, tomatoes, and peppers. Her sons often assisted in the canning process and worked with Grandpa out in the garden. Additionally, she made ketchup, beer, and wine (for Grandpa), all stored in the musty cellar below the house.

The cellar was dark and damp, yet it fascinated me. My older sister, Jo Rae, and I didn't spend much time there, but we heard numerous unpleasant stories from our dad and uncles. They recounted experiences of Grandpa butchering animals for dinner and the brothers crushing grapes with their feet to make wine, leaving stains that would linger in their memories long after they faded from their feet and ankles.

Grandpa liked to drink, mainly beer, wine, and cider. He was paid every Friday from his job at the foundry, a factory that produced metal casings. After finishing his Friday shift, he'd meet his Italian friends, or paisanos, at the local bar. Grandpa was generally a happy drunk, often staggering home late at night, bellowing Italian songs, and sometimes bringing home stray dogs and cats. Granny would give him hell, embarrassed that everyone on Ellicott Street knew when 'Jim' was coming home. Occasionally, he'd stumble in after midnight with a few friends. He'd wake the family to announce they were hungry, prompting my grandmother to whip up pasta with oil and parmesan. My dad, Joseph, was the wine boy, lumbering down two flights of stairs to fetch a gallon of wine for them while his mother cooked. He felt his mom was a saint for putting up with it, feeling helpless to change the situation. However, one night, he decided he had enough of the late-night chaos. The last time 'Joe' went down the dark, clammy cellar steps, at nine years old, to bring up a bottle, he made a bold choice: he opened all the spigots and drained the wine and cider, flooding the basement floor. Despite his mother's reputation as a stern disciplinarian, neither of his parents reprimanded him that night, even though it would've been considered a significant mistake for a young boy. His mother likely protected him while also feeling relieved that he had taken charge. After that, Grandpa never brought his friends over for "midnight" dinners, and my dad never had to fetch wine for him again.

Decades after the days of homebrew, I recall, on rare occasions, my grandpa indulging in too much wine or beer when my grandparents visited us in Houston. He'd sit in his favorite chair, belting out Italian songs while my father closed the windows, attempting to shut out the shame and embarrassment he still felt from childhood. However, my experience was one of great pleasure, as I was delighted to see this silent man express himself with such fervor.

Later in life, as I delved into my family history, I discovered that my great-grandfather and his sons used their strength and influence to get whatever they wanted. There were rumors of possible ties to the Mafia, perhaps stemming from their roots in Sicily. However, I never witnessed that side of the family during our visits. I enjoyed the time spent with my grandmother's brothers when they came over. We would play cards, share meals and they'd all drink and act merry. The oldest brother often slipped my sister and me a twenty-dollar bill.

Many of us, the children of our parents' generation, have chosen not to repeat the cycle of abuse. We recognize the importance of looking inward to better understand ourselves, realizing that the psychological defenses we developed for self-protection don't serve us or our loved ones. From my unique perspective, I've also explored the shadows of both my parents and learned a great deal through conversations with them, particularly my mother, which has helped me understand their actions throughout my life. The legacy of abuse that my grandparents experienced, especially my grandmother, was passed down through the generations and influenced my family of origin, albeit in a much more diluted form.

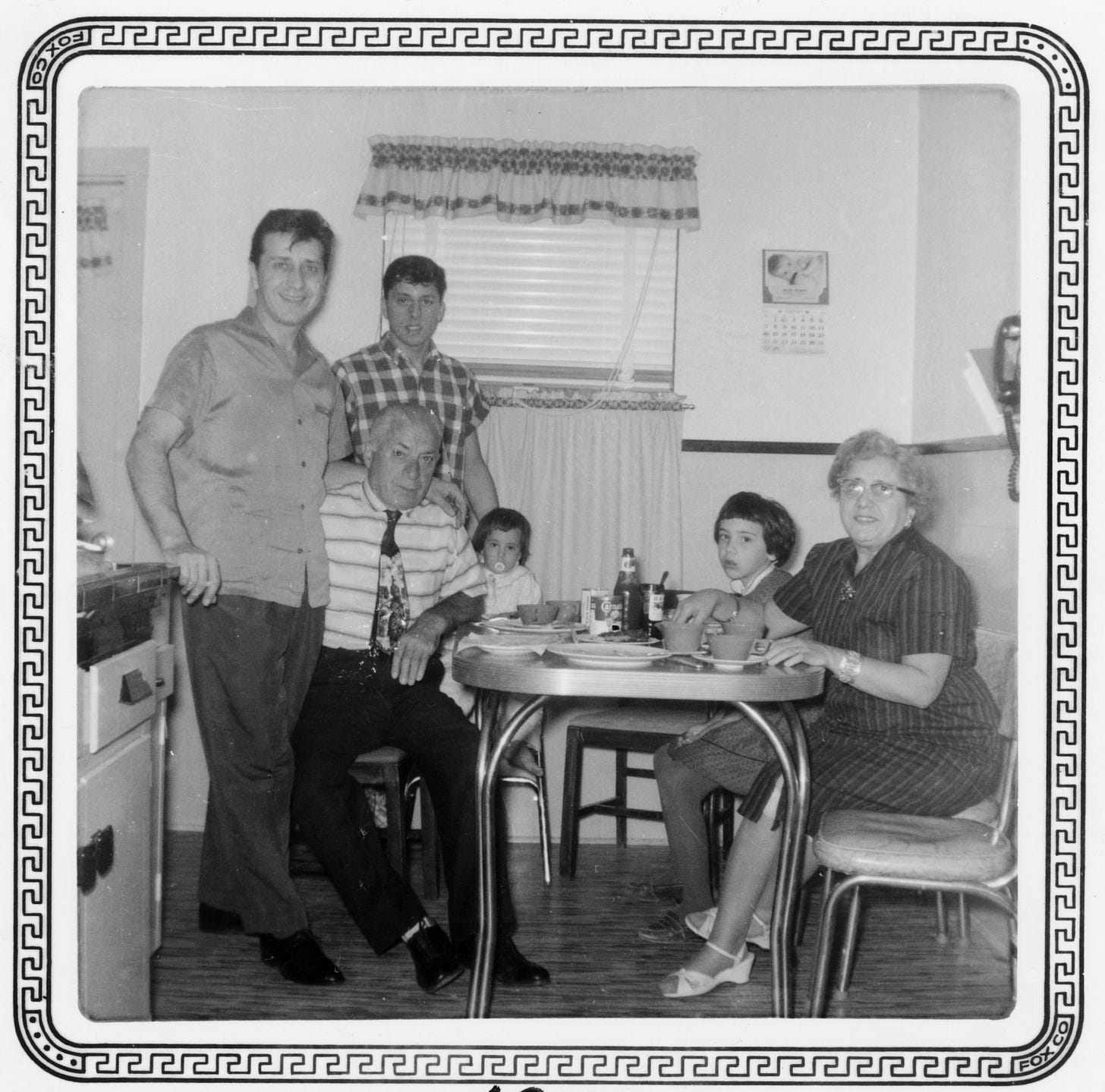

In the summer, we'd arrive from Texas either by car or by train. Usually, a group of relatives would greet us at the station: my grandmother’s sister and brothers, their spouses and children, along with my father’s brothers, their spouses and children. If they weren’t at the station when we arrived, we'd visit them during our two-week stay. Regardless of the time we got in, food was always waiting for us. When we sat down for scheduled meals, there was little conversation about current events or the weather, as my father preferred to avoid topics that might agitate anyone and ruin our appetites.

I have fond memories of clam bakes with the clan in Buffalo, where my grandmother's brothers lived next door to each other with their wives. They were quite the pair, always cutting up and being silly, telling dirty jokes, drinking beer, and eating lots of pasta. Being with our cousins in Batavia was our great escape. We'd hang out all day, riding bikes, playing with dolls, and having picnics at the park. We occasionally spent the night, staying up late and enjoying pasta or lasagna, continuing the family tradition.

The house on Ellicott Street was always cozy and filled with the aroma of homemade Italian food. Granny and Grandpa made pasta from scratch while I eagerly watched, waiting for my own handful of dough. Although the recipes have been passed down through generations, none compare to the taste of Granny's cooking—especially her sauce, which she stirred with a steady and loving hand.

As I meandered through the yard and up to the back porch, the aroma of fresh garlic, basil, and peppers simmering in a pasta sauce filled the air. I walked through a screen door end entered the kitchen, which was the heart of our gatherings. There, we would congregate around the table - my father and I, Granny and Grandpa, along with various relatives - playing cards for hours. Grandpa would pop open a bottle of beer, take a gulp, let out a satisfying belch, and then pass the bottle to me for a sip. We took our card games seriously, playing Rummy 500 or Gin Rummy and always keeping score. Granny would sometimes shake her head, exclaiming, "I've got a hand like a foot!" Was she bluffing?

In the kitchen, the women gathered. Aunt Jennie, my grandmother's older sister would banter back and forth with Granny about any and everything. Sometimes Mary, Uncle Michael's wife, and my mom, Rae, would listen from the sidelines, occasionally interjecting an opinion. However, the conversation primarily served as a forum for the sisters to discuss menopause and hot flashes, and how they suffered, hanging their heads low and shaking them, muttering "miska, miska" in their typical Italian fashion.

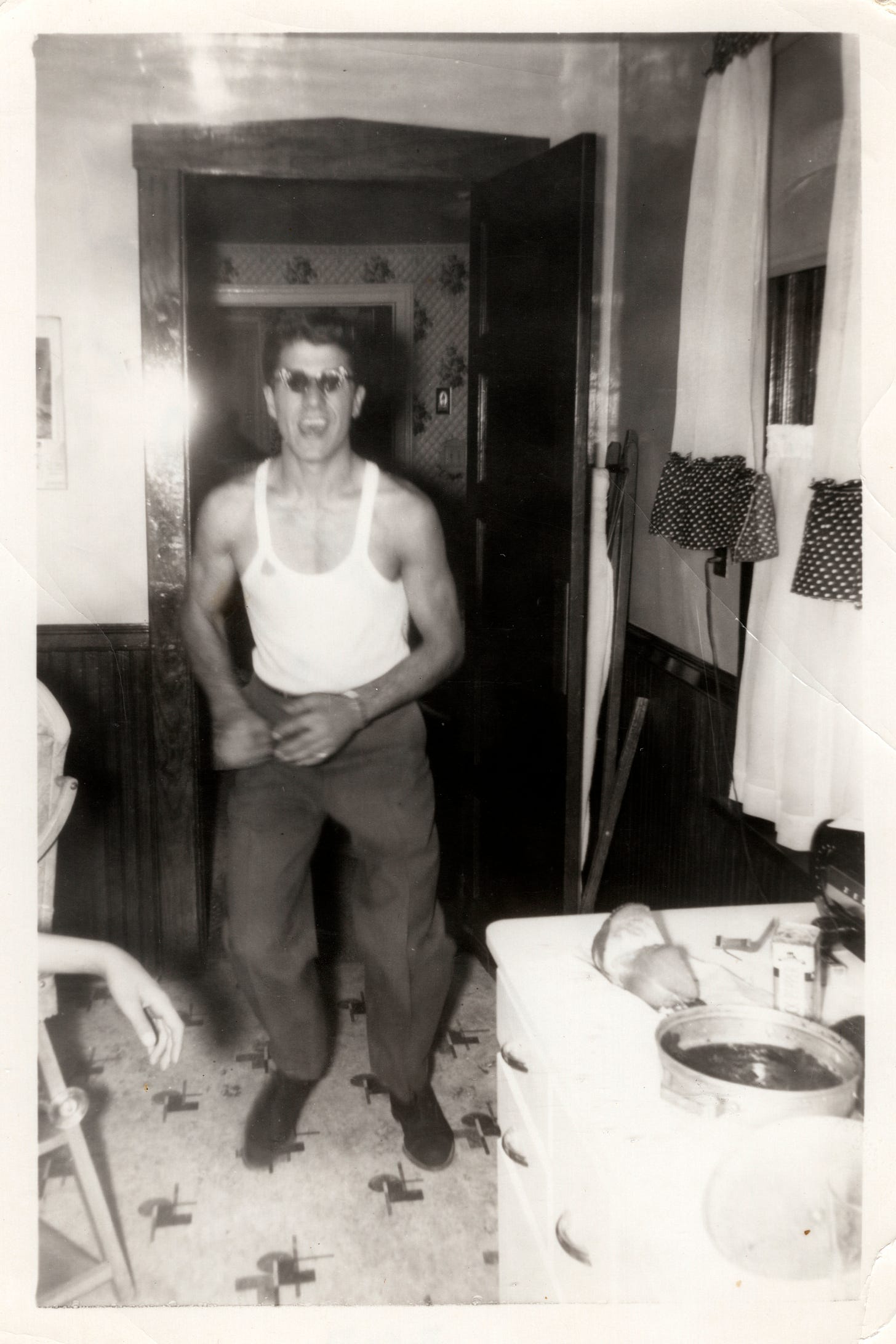

During his teenage years, my dad learned to dance from Anna, Aunt Jenni’s daughter. He became an excellent dancer. Years later, my parents met on the dance floor at Lackland Air Force Base, where my dad was stationed, and my mom worked as an office clerk during the day. They often danced to jazz during the Saturday night jam sessions. They were incredibly compatible and captivating on the dance floor, to the extent that people would gather around to watch them. As a couple, they were striking—both incredibly good-looking and sharp dressers. In those days, my mother was outgoing, while my dad was friendly but a bit shy.

Michael was the youngest of my father's brothers. I had a crush on him from the time I was four until I was sixteen. He was tall, dark, and handsome, and he always gave me special attention, probably because he knew I adored him. He playfully called me Theresa Nell to tease me, knowing I hated my middle name. When he flashed his charming smile, I couldn't help but forgive him.

Uncle Michael was an accomplished jazz drummer. When I was young, maybe four years old, he lived with us for a while in San Antonio. My dad took him to a music store and bought him his first set of drum brushes. Michael practiced every day, playing on top of my mom's Life Magazine stacks on the coffee table. He was a natural, mostly self-taught and never read music. When he returned to New York, he tutored under Johnny Brunson, a blind, jazz piano player. Brunson gave him structure, and jazz improvisation lessons. Even though he no longer lived on Ellicott Street, he kept a drum kit in an upstairs bedroom. When our family was in Batavia for my grandparents fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1974, he played the drums for us, with me crooning over this elegant, angular man with the nasal voice and crooked smile.

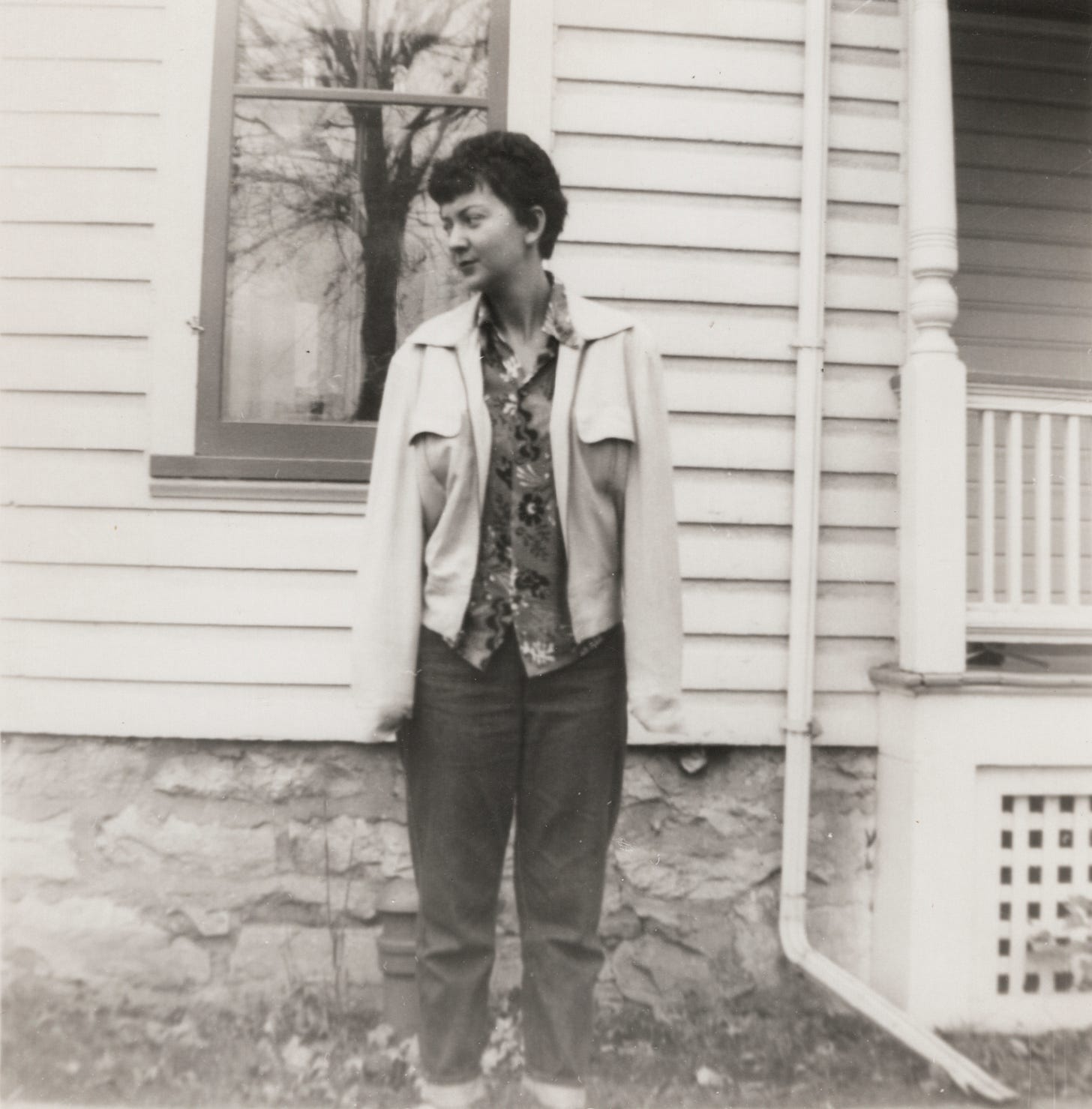

Uncle Michael’s wife, my Aunt Mary, was a pretty and slender woman with a wry sense of humor, short black hair, and blue eye shadow. She taught Braille to blind children and drove a 1964 Thunderbird convertible. Mary would take my sister and me away from our grandparents and parents for a day, pulling down the car's top as we visited other relatives, ran errands, or simply hung out. Those outings made me feel special. This beautiful, stylish woman with the classy car, generous spirit, and handsome husband wanted to spend time with me, and I felt more mature than my nine years.

I learned about my father's older brother, Uncle Lou, primarily through stories passed down from family, particularly from his wife, Carmine. They moved from Batavia to Colorado and then to New Mexico before my first memory of visiting Batavia at the age of four. Over the past several years, Aunt Carmine and I have grown close, and I sometimes stop by to see her on my way north to Taos. She's a wonderful storyteller and possesses a rich knowledge of our family history. Through her sincere yet brutally honest manner, she's shared countless stories, teaching me even more about my roots and how our shared history has shaped my father's life and, ultimately, my own.

Throughout his life, Lou often helped the family, especially financially. During high school, he left for three months to work on a farm in Batavia, giving his parents money to help support the family. My dad and Anthony also worked after school, contributing their earnings to the family pot, and at the end of the week, they were rewarded with a quarter to go see a movie and buy a bag of popcorn. Later, Lou continued to send money home so that Michael wouldn’t have to work. Michael had a very different upbringing compared to his three brothers, as he was sixteen years younger than his oldest brother.

Lou believed that my dad, Joe, was a great artist. He would use long rolls of paper, similar to the kind used to line cupboards, and draw on them for hours. There was a laundry room behind the kitchen and one day, the stove caught fire on the other side of the wall, which caused the laundry room to burn. Unfortunately, Dad's drawings were in that room, and they were all destroyed in the fire. How I would love to have those drawings.

Anthony, the third son, moved to Los Angeles in the early sixties with his wife, Marianne, and their sons, Mark and Michael. He became a celebrity barber and was renowned for his love of music, his excellence in tap dancing, and for "giving the best damn haircut in Rancho Mirage!" He was affectionately known as "Tony the Dancing Barber."

During a visit before they moved, when I was six years old, their oldest son, Mark, poured sand in his parents' gas tank, which made Anthony furious. He yelled and moved about frantically, a common reaction for the excitable DiMenno family.

Years later, after my parents' divorce and my father's subsequent marriage to another woman, my cousin Michael lived with my dad in Tennessee for an extended period. He and I felt an instant connection when I visited, and through the following years, we grew very close.

Over the past year, I dedicated a significant amount of time to archiving my family’s history. I've enjoyed going through old photographs, documents, and letters, contemplating who else might have touched them. My mother saved everything, including my father's archives, which provided me with a wealth of material to explore. I've experienced my father's family more directly than my mother's, so I chose to focus on my Italian heritage for this story. I also have a collection of letters exchanged between my mother and her sisters, friends, and in-laws, as well as envelopes filled with old negatives that I still need to sort through. Her story is incredibly profound, marked by extreme loss, trauma, and ultimately, liberation.

On a summer day in 1963, the only people at home were my grandpa, who was asleep in his recliner, and my mom and grandmother, who were in the kitchen talking. I could hear their muffled voices through the screen window and curtains, but they were just out of sight, allowing me to keep them nearby yet at a distance. A narrow walkway ran from the backyard along the side of the house to the sidewalk in front. At six years old, I pretended to have an angelic voice, singing the lyrics to the popular early sixties song "Downtown." "Where all the lights are bright ... downtown. Forget all your troubles, forget all your cares, and go downtown." As I waltzed along the pathway, I imagined being beautiful and eighteen, with blue eyes, an upturned nose, and blonde hair teased perfectly at the top, cascading over my shoulders in a stylish upward flip. I envisioned attracting any boy I wanted, embodying the Barbie Doll image that every little girl dreamed of.

I loved the upstairs with cool breezes circulating through the open windows and the cafe curtains gentle sway. The furniture was old and sturdy, filling the air with the scent of nostalgia. During the day, I could retreat upstairs to find solitude, as all the activity took place downstairs. In between family gatherings and meals, there were moments of laziness where I could relax and embrace the comfort of so much love and warmth. I recalled a beloved bond of family, of humanity and despite our differences, we are all the same, needing love, comfort and a place to call home.

Your grandmother and my grandfather were brother and sister

I just received that article, and I loved it. I'm Joe Joe Monte, Rose Marie's third son. It was a priceless blessing to read the article. We lived around the corner from Aunt Theresa and visited often. I'm 61 years old and family history seems to hold more value and to honor the LEGENDS that went before us.